Some bodies absorb iron even when they don’t need more. This process isn’t driven by diet alone. The issue begins with how the body regulates iron through hepcidin, a hormone produced in the liver. When functioning properly, hepcidin controls absorption based on iron levels and needs. In people with iron overload conditions, this regulation fails. The body continues to absorb iron from food, storing it in organs. Over time, the accumulated iron begins to damage tissue. The liver, heart, pancreas, and joints are especially vulnerable. This damage builds gradually and may not show symptoms early. By the time fatigue, joint pain, or irregular heartbeat appear, injury is already underway. This is why iron overload is often referred to as a silent condition in its early stages. Without detection, this simple mineral becomes toxic.

Hereditary hemochromatosis can go unnoticed for decades

Hereditary hemochromatosis can go unnoticed for decades. It’s often inherited through mutations in the HFE gene. These mutations cause the body to absorb more iron than necessary, leading to excessive storage. Individuals with two mutated copies are at higher risk, but not all develop symptoms. Men are usually diagnosed earlier than women, partly because menstruation naturally reduces iron. For many, the first sign is a vague symptom—exhaustion, unexplained pain, or loss of libido. These clues are often misattributed to aging, stress, or unrelated conditions. Blood tests may appear normal until ferritin and transferrin saturation levels are specifically checked. That’s why targeted testing is essential for diagnosis. Without genetic testing or a family history, the condition might never be identified in time. Once discovered, it shifts how a person must think about food, health, and monitoring.

Iron doesn’t just stay in the blood—it settles into tissues and organs

Iron doesn’t just stay in the blood—it settles into tissues and organs. This distinction explains the long-term risks. While iron is essential for oxygen transport and cell function, surplus iron behaves differently. It reacts with oxygen, creating free radicals that damage cells. This oxidative stress accelerates organ aging and dysfunction. In the liver, excess iron can lead to fibrosis, cirrhosis, or even cancer. In the heart, it disrupts rhythm and weakens muscle function. The pancreas may stop producing insulin, causing diabetes. Joints become inflamed as iron accumulates in cartilage. None of this happens overnight. The problem grows with every unregulated meal, every unnoticed symptom. That’s what makes the condition deceptive. People feel well while damage continues silently. A normal life is possible, but not without management.

Fatigue is often the first symptom people ignore

Fatigue is often the first symptom people ignore. It’s subtle and easy to rationalize. Long workdays, poor sleep, or emotional stress can all mask iron overload. But this fatigue feels deeper—persistent, not relieved by rest. Some describe it as a fog, making concentration difficult. Others feel their muscles weaken without cause. Even walking up stairs becomes harder. This symptom may appear years before diagnosis. Because fatigue is so common, it’s rarely linked to iron levels unless a doctor suspects it. That’s why listening to persistent tiredness matters. It may not be the iron itself causing tiredness, but the silent strain it places on vital organs. When iron impairs heart function or hormone regulation, the whole body slows down. Fatigue isn’t just a signal—it’s the body asking for intervention.

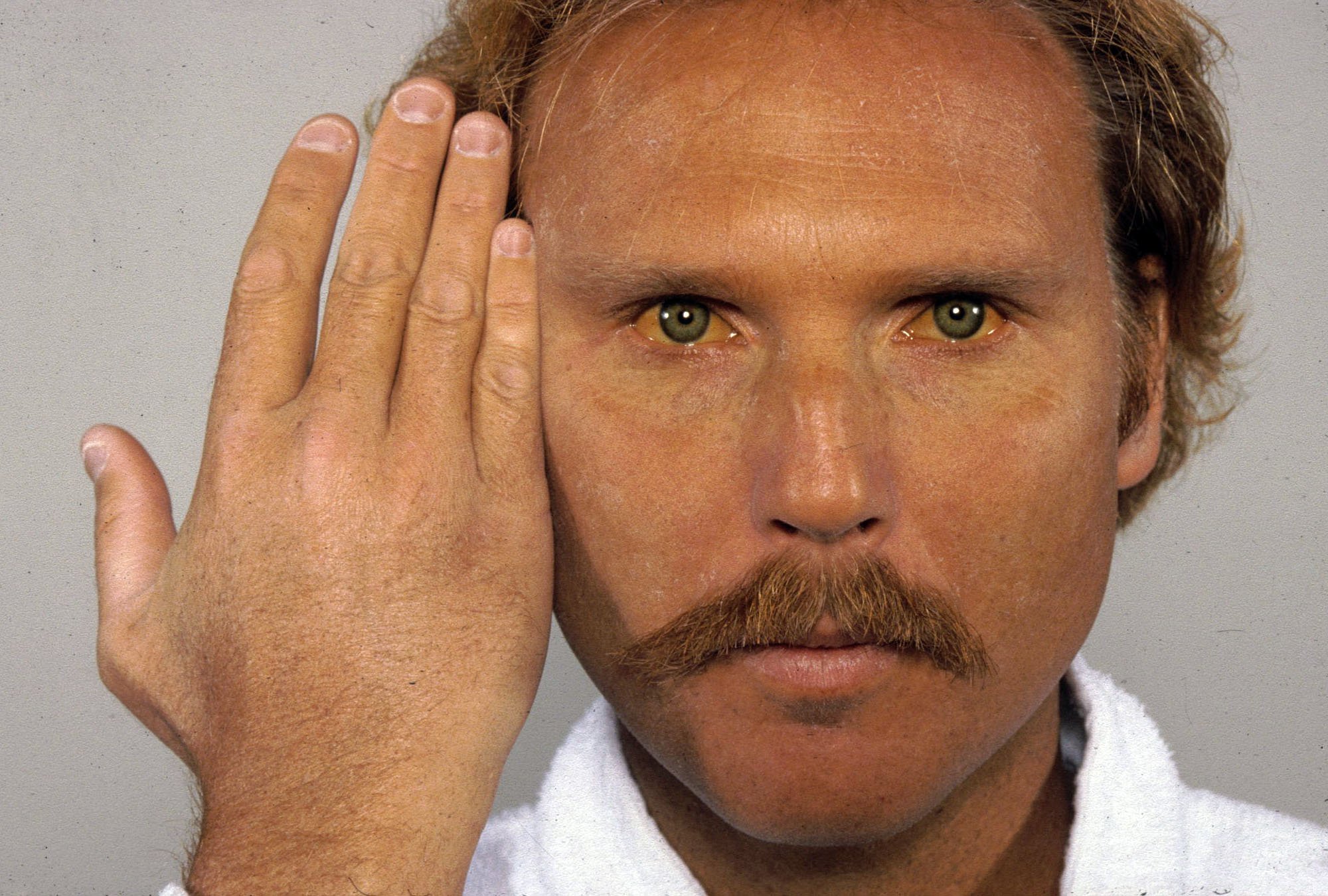

Skin tone changes can reveal what blood tests miss

Skin tone changes can reveal what blood tests miss. In some cases, iron overload causes skin to darken or take on a bronze hue. This occurs as iron collects in skin tissue and alters melanin production. The change is gradual and often seen on the face, neck, or hands. People might think it’s just a tan or sun damage. In truth, it’s one of the few visible signs of internal imbalance. This symptom was historically called “bronze diabetes” when linked with iron-induced diabetes. While modern medicine no longer uses that term, the association remains important. If unexplained pigmentation appears, especially alongside fatigue or joint pain, it’s worth investigating. A shift in skin tone may be cosmetic—but it might also reflect deeper biological stress.

Elevated ferritin levels are not always caused by excess iron

Elevated ferritin levels are not always caused by excess iron. This makes diagnosis more complex. Ferritin is an iron storage protein, but it also rises during inflammation. Conditions like liver disease, infection, or cancer can elevate ferritin without iron overload. That’s why a single high reading doesn’t confirm the problem. It must be evaluated with transferrin saturation, which shows how much iron is actively circulating. Both numbers together give a clearer picture. In real cases of overload, transferrin saturation is typically above 45 percent. Many patients live with high ferritin for years without knowing if it’s iron or something else. Understanding the context around lab values is critical. Misdiagnosis can lead to unnecessary dietary changes or missed treatment opportunities. Ferritin is part of the puzzle—not the full story.

Some people with high iron never develop damage

Some people with high iron never develop damage. This is one of the condition’s paradoxes. Genetic mutations don’t always equal disease. Environmental and lifestyle factors matter. Alcohol consumption, viral infections, or poor liver health can accelerate problems. Others live decades with elevated levels and remain symptom-free. Why this happens isn’t fully understood. It may relate to how the body distributes iron or manages inflammation. It also depends on gender, age, and other health conditions. This uncertainty makes personalized care essential. Not everyone needs aggressive treatment, but monitoring is crucial for all. Just because there’s no damage now doesn’t mean risk is absent. Health depends not just on numbers but on patterns—how iron behaves over time.

Phlebotomy is the standard treatment, but not everyone tolerates it easily

Phlebotomy is the standard treatment, but not everyone tolerates it easily. The process involves removing blood regularly to lower iron stores. It mimics blood loss and tricks the body into using stored iron. Over time, this reduces levels to a safer range. Some people tolerate it well; others experience fatigue, dizziness, or needle anxiety. It requires discipline—weekly sessions at first, then maintenance every few months. Skipping appointments can reverse progress. For those unable to undergo phlebotomy, iron chelation is another option, but it comes with its own side effects. There’s no one-size-fits-all solution. The key is consistency, not perfection. Early-stage patients often see significant improvement with routine care. The treatment may seem simple, but its long-term impact can be life-saving.

Diet alone won’t cause iron overload, but it can make it worse

Diet alone won’t cause iron overload, but it can make it worse. People with the condition must be careful with iron-rich foods. Red meat, organ meats, and fortified cereals can rapidly add to iron stores. Vitamin C enhances absorption and should be limited during meals. Alcohol increases liver stress and should be minimized. That said, food isn’t the root problem—it’s absorption. Still, mindful eating helps reduce the burden on organs. Unlike anemia patients who are told to eat more iron, those with overload need the opposite. This reversal confuses many and often leads to accidental mismanagement. It’s not about fear—it’s about balance. Understanding which foods to enjoy and which to reduce creates a manageable path. Diet won’t cure iron overload, but it’s part of long-term care.

Early detection can prevent irreversible organ damage

Early detection can prevent irreversible organ damage. That’s the quiet truth behind most chronic conditions. For iron overload, time is the main enemy. The body won’t alert you with pain or urgent symptoms. Instead, harm accumulates silently—until it’s too late. A simple blood test can change that. For families with history of the condition, screening should start early. Primary care providers must think beyond anemia when they see iron levels. This isn’t just about avoiding disease—it’s about protecting energy, memory, fertility, and longevity. A diagnosis doesn’t mean disaster. It means awareness. From there, lives can be rebuilt with informed care and vigilance.