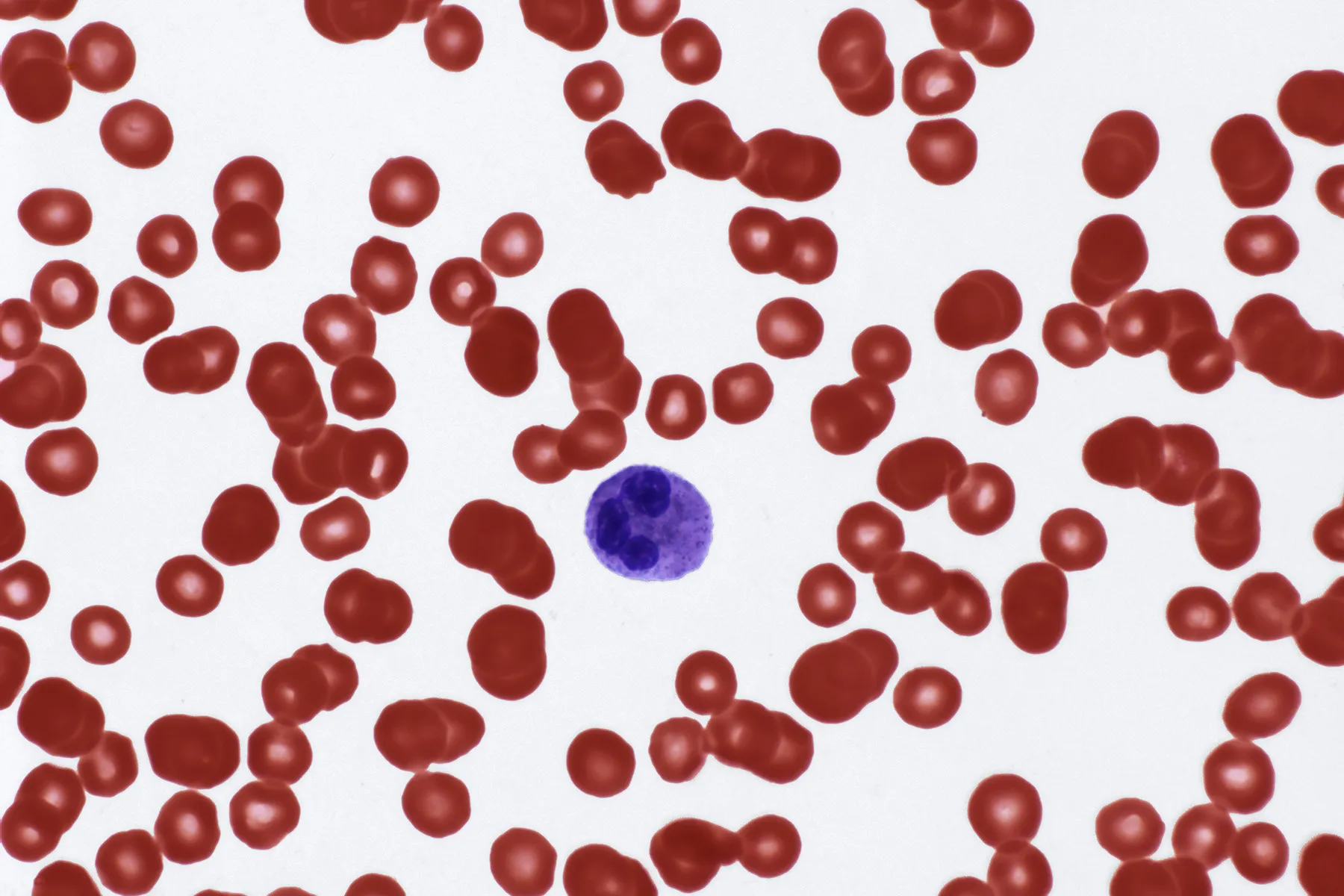

The human body’s intricate defense system, orchestrated by an army of white blood cells, is a marvel of biological engineering. These cells, also known as leukocytes, are the vigilant sentinels that patrol our bloodstream, ready to identify and neutralize pathogens, foreign invaders, and abnormal cells. When their numbers dip below a certain threshold—a condition known as leukopenia—it signals a potential vulnerability in the body’s protective shield. This reduction can be a perplexing symptom, pointing to a vast and diverse array of underlying causes, ranging from temporary, self-resolving issues to chronic and serious medical conditions. Understanding the potential origins of a low white blood cell count is a crucial step in unraveling a patient’s health puzzle and determining the appropriate course of action.

Understanding the potential origins of a low white blood cell count is a crucial step in unraveling a patient’s health puzzle.

A significant portion of leukopenia cases can be traced back to problems originating in the bone marrow, the very factory where white blood cells are manufactured. The bone marrow is a complex and highly active tissue, responsible for producing not only leukocytes but also red blood cells and platelets. Any disruption to this vital production line can have far-reaching effects. For instance, certain viral infections, particularly those that are systemic, can temporarily suppress bone marrow activity. Viruses like Epstein-Barr (EBV), which causes mononucleosis, or even influenza can lead to a transient drop in white blood cell counts as the body’s resources are diverted to combat the immediate viral threat. In more severe cases, bone marrow failure, stemming from conditions like aplastic anemia, leads to a profound and widespread reduction in blood cell production. This is often an autoimmune process where the body’s own immune system mistakenly attacks the bone marrow stem cells. Exposure to certain toxins, such as benzene, or a history of radiation therapy and chemotherapy for cancer treatment can also damage the bone marrow, leading to a diminished capacity to produce an adequate number of white blood cells.

The bone marrow is a complex and highly active tissue, responsible for producing not only leukocytes but also red blood cells and platelets.

Another cluster of causes relates to the destruction or consumption of white blood cells after they have been produced. The lifespan of a white blood cell is relatively short, and if they are being used up faster than the bone marrow can replace them, the circulating count will inevitably fall. Chronic, widespread inflammation is a classic example. Conditions like lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, which are autoimmune in nature, cause the immune system to mistakenly attack healthy tissues. This constant state of alert and subsequent cellular battle can deplete the body’s reserve of leukocytes. Severe, overwhelming infections, a state known as sepsis, also lead to a massive consumption of white blood cells as the body desperately tries to fight off the invading pathogens. In this scenario, the initial high count of white blood cells in response to the infection can suddenly drop as the bone marrow’s production capacity is outpaced by the sheer demand. This rapid decrease is often a dire sign of a weakening immune response.

Chronic, widespread inflammation is a classic example.

Medications are another frequent and sometimes overlooked culprit behind low white blood cell counts. A wide array of prescription drugs, from antibiotics like minocycline and chloramphenicol to certain psychiatric medications and diuretics, can have this effect as a side-effect. The mechanism of action varies. Some drugs directly suppress bone marrow function, while others trigger an allergic or hypersensitivity reaction that causes the body to destroy its own leukocytes. For a person undergoing chemotherapy, a low white blood cell count is not a surprise; it is an expected and managed consequence of the treatment, as the potent drugs are designed to kill rapidly dividing cells, including cancer cells and, unfortunately, the rapidly dividing cells in the bone marrow. However, for a patient on long-term medication for a chronic condition, the link may not be immediately obvious, and the physician must consider the drug regimen as a primary suspect when investigating leukopenia.

For a patient on long-term medication for a chronic condition, the link may not be immediately obvious.

Certain nutritional deficiencies can also play a role in the development of leukopenia. The bone marrow requires a steady supply of specific nutrients to function optimally. A deficiency in essential vitamins like B12 or folate can impair the production of all blood cells, including white blood cells. Similarly, severe malnutrition, in general, can compromise the body’s ability to produce an adequate immune response. These deficiencies are often seen in individuals with conditions that affect nutrient absorption, such as celiac disease or Crohn’s disease, or in those who follow extremely restrictive diets without proper supplementation. Correcting these deficiencies, often with dietary changes and supplements, can sometimes resolve the low white blood cell count entirely. This highlights the foundational importance of nutrition in maintaining a healthy immune system.

A deficiency in essential vitamins like B12 or folate can impair the production of all blood cells.

Genetic factors and inherited conditions can also predispose an individual to have chronically low white blood cell counts. Some individuals are born with conditions that affect bone marrow function or lead to the rapid destruction of leukocytes. While some of these conditions are rare and diagnosed early in life, others might manifest later and be more difficult to pinpoint. For example, specific forms of congenital neutropenia result in a lifelong lack of neutrophils, a key type of white blood cell. These conditions require careful management and often involve treatments that stimulate the bone marrow to produce more cells. The investigation into a person’s low white blood cell count often includes a thorough family medical history to rule out or identify these inherited possibilities.

The investigation into a person’s low white blood cell count often includes a thorough family medical history.

Another category of causes includes spleen-related issues. The spleen acts as a filter for the blood, and if it becomes overactive—a condition known as hypersplenism—it can trap and destroy an excessive number of blood cells, including white blood cells. The spleen might become enlarged due to various conditions, such as liver disease, certain infections, or blood cancers. An overactive spleen can lead to a misleadingly low count of circulating white blood cells because they are being sequestered in the spleen rather than circulating freely in the bloodstream. Addressing the underlying cause of the spleen’s enlargement is the primary way to correct this type of leukopenia.

The spleen acts as a filter for the blood, and if it becomes overactive—a condition known as hypersplenism—it can trap and destroy an excessive number of blood cells.

Lastly, certain malignant diseases and cancers, particularly those that affect the blood and bone marrow, can directly cause leukopenia. Leukemia, for example, is a cancer of the blood-forming tissues, including the bone marrow. In leukemia, the bone marrow produces an abundance of abnormal, immature white blood cells that are not functional. This overproduction crowds out the healthy, mature cells, leading to a drop in the functional white blood cell count. Other cancers that metastasize to the bone marrow can also displace the healthy blood-forming cells, leading to a similar outcome. The presence of a low white blood cell count alongside other symptoms like unexplained bruising, fatigue, or recurrent infections is often a red flag that warrants a deeper investigation for a potential hematological malignancy.

The presence of a low white blood cell count alongside other symptoms like unexplained bruising, fatigue, or recurrent infections is often a red flag.

The diagnostic process for leukopenia is rarely straightforward and often requires a comprehensive approach. A physician will typically begin with a detailed patient history, including a review of all medications, diet, and any recent illnesses. This is followed by a physical examination and a series of blood tests to confirm the low count and to identify which specific type of white blood cell is affected. If the cause is not immediately apparent, further investigations might be necessary, such as a bone marrow biopsy, which provides a direct look at the cell production process. This methodical and often complex diagnostic journey is essential for accurate identification of the root cause.

This methodical and often complex diagnostic journey is essential for accurate identification of the root cause.

A low white blood cell count is not a diagnosis in itself but rather a sign that something is amiss within the body’s complex and interconnected systems. The range of potential causes, from simple viral infections to serious bone marrow conditions, necessitates a careful and systematic medical investigation. Proper diagnosis and treatment are crucial to restoring the body’s protective immune shield and safeguarding a person’s health against future threats.